When George Carper was a boy, he often rode his bicycle from his home in Kirkwood to the grass airport that was just west of the Route 66 bridge on the Meramec River.

"I watched the airplanes and said I wanted to do that one day," George recalled. "They laughed."

They laughed because he was a kid on a bicycle. A black kid on a bicycle. In the 1930s.

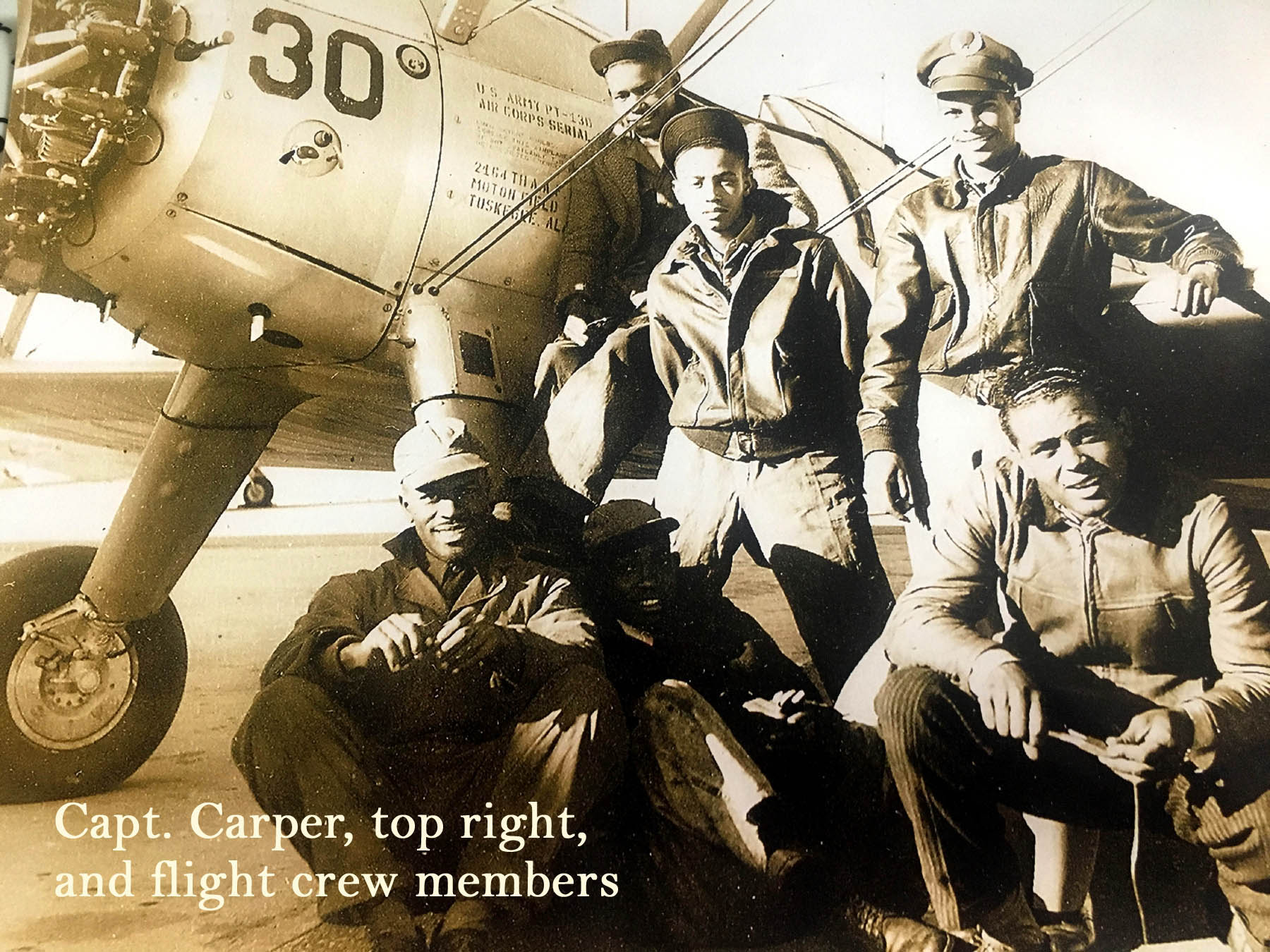

When the United States entered World War II, George was a student at Tuskegee University in Alabama, just starting his training in aircraft and engine mechanics. Only 16 years old, he soon found himself in the U.S.450 now-famed Tuskegee Airmen, the black fighter pilots who fought with great distinction in the skies over Europe.

And George became a pilot, too. He was too young to be sent to Europe and too valuable to the training efforts at Moton Field. But he had to do flight checks on those trainers, didn't he? By the end of the war he was qualified to fly the Army's training aircraft and a couple of the fighters -- such as the fearsome Mustang P-51 in which some of the Tuskegee Airmen created their legends.

Lauded during their service, after the war the airmen returned home to the racism that existed before they wore uniforms. Respect for their service has been renewed in recent years, partly due to the release of the honored 1995 movie called The Tuskegee Airmen.

The mix of patriotism and prejudice that colored their service still makes it difficult for some of the surviving airmen to talk about their service.

" It wasn't something they really talked about," said Carole Carper, George's daughter. "His brother, Johnny Briggs, also was a Tuskegee Airman, so we had two of them at our table every Thanksgiving and Christmas. I think there was a lot of pain associated with it."

Carole did not know her father and uncle were World War II heroes until she was nearly grown up. "I started to realize that in high school or college when people started interviewing dad about the Tuskegee Airman experience. We always had that picture of him standing by his plane in the family room. We knew he was in the service and knew how to fly."

Why he is so reluctant even today to talk about the Tuskegee chapter of the American experience?

"That is very consistent with him. He never said a poor word. I don't know if he thought he was protecting his family in hope we would never have to experience that. When you have had a lot to go through, you don't want to talk about it because you can't change it," Carole said. "Race, with dad, was always a sensitive subject."

Kirkwood Kid

George's family lived in the neighborhood around Van Buren and Monroe avenues in Kirkwood, next to the Missouri Pacific Railroad tracks. George and other kids often followed the tracks out to what they called the cave -- the historic railroad tunnel that is now part of the National Museum of Transport.

George's father started the Carper Casket Company in 1932 to serve the region's black funeral homes. Now a distributor, until 1942 the company manufactured caskets. The company is still in business at 3204 Samuel Shepard Drive near Grand Center in St. Louis in a vintage building that was bought from Anheuser-Busch Co.

"Kirkwood was a good place, compared to many places, as far as relationships back in the 20's and 30's. That's something I tell people," George recalled as he talked in his room at the Missouri Veteran's Home in Bellefontaine Neighbors. "We lived in a mixed neighborhood. When I was growing up we all played together."

George was born with a knack for technical and mechanical things. He learned photography when very young and also built model airplane kits -- the old-fashioned kind that consisted mostly of pieces of wood.

"When I got tired of them I'd fly them off the third-floor roof -- put a match to the tail and watch them go down. I spent $40 one time on a little gasoline engine and put it on a plane. The second time we took it out to the park and flew it, it crashed. There went all my money."

Real airplanes attracted his attention, too.

"There was a fellow named (Jack) Steuby who had a lot of industry in town. He had a little airport on the edge of Kirkwood across the Meramec. We used to ride bikes down Geyer, go out the highway and cross the bridge. The airport was on the right side," George said.

Kirkwood's schools were segregated in George's day. From kindergarten through fourth grade he attended the Booker T. Washington School on Adams Avenue near Geyer Road. He finished his elementary education at J. Milton Turner School in Meacham Park. For high school, Kirkwood paid tuition for black students to attend high school in St. Louis.

George graduated from Sumner High School in 1941 at the age of 15. His father gave him two choices.

"My dad said you are going to work or you are going to school," George said. "I said, 'I'm going to Tuskegee.'"

Tuskegee University in Tuskegee, Alabama, was a black college that had earned a national reputation.

"They had the most highly-rated school," George said. "Tuskegee was a little town smaller thank Kirkwood -- 6,000 to 8,000 people, all black. Tuskegee was surrounded by whites, but if you stayed in Tuskegee you had no problems. Anytime you went out of town, you weren't worth s--- no more. I went down there thinking it wouldn't be as bad as they say. S---, in some places down there it was worse."

George enrolled in the university as an airframe and engine student and started getting hands-on experience with aircraft based at Moton Field.

"Then the war broke out and they put me in the reserves when I was 16. I got to be a flight chief. I had 30 airplanes and a crew of 30 men and women," he said.

The U.S. Army based its black pursuit fighter squadron at Tuskegee University because it already operated a respected aeronautical training program. (The Air Force became a separate military branch in 1947.)

The Army's "Tuskegee Experiment" trained African-American pilots, navigators, bombardiers, instructors and maintenance staff. By the end of the war it had trained about 1,000 pilots and 14,000 other skilled personnel -- navigators, bombardiers, instructors, aircraft and engine mechanics, control tower operators and support staff.

Flight training was completed at Moton Field by 992 pilots during World War II. Of the 355 pilots deployed overseas, 84 died and 32 were captured as prisoners of war.

Tuskegee Airmen flew more than 15,000 sorties on 1,5798 combat missions in Europe and North Africa and earned three Distinguished Unit Citations and more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses. The Airmen were credited with shooting down 112 enemy aircraft, destroying 150 on the ground and damaging another 148. They destroyed 950 rail cars and ground vehicles, sank 40 boats and barges and put one destroyer battleship out of action.

The performance of the black pilots and ground crews was said to have fostered the integration of the U.S. armed forces after the war.

George eventually earned a pilot's license but spent the remainder of the war at Moton Field. "The trouble was, I was there early and was pulled out of school to do maintenance," he said. "They said, 'We know if you fix it, it'll work.'"

Tuskegee's conversion to a military base altered the area's social dynamics. "There was a lot of ill feelings, but if you had a uniform on you weren't treated the same as if you didn't. That made some big changes down there.," George said.

To fly

George was the flight chief for one of three flights of training aircraft at Moton Field.

They started working on the Boeing-Stearman PT-13 and PT-17 biplanes and Fairchild PT-19 single-wing aircraft. They later moved up to the Vultee BT-13 Valiant advancer trainer.

"In primary training they had the PT-13 for the first 60 hours of flying, then they went to the BT-13. Those biplanes were fun. Those were what I started on," George said. "The BT-13 was a beautiful plane but it had no power."

Some of the ground maintenance crewmen stole a few minutes of flight time here and there, he said. "When you are working on them you graduate to taxiing them around. In the early morning when we had to pre-flight and warm 'em up, a lot of guys would taxi a little fast, just enough to get the wheels off the ground. Then they'd shut down and come back in. A lot of the guys could fly but hadn't had lessons."

Flight crews had to develop tricks to service machines that had been designed for flight with maintenance as an afterthought.

"Some of the spark plugs you couldn't get your hands on. You could get a wrench on them but not your hands," George said. "Every nut and bolt had to be safety-wired. There is nothing in the world better than that, but you have tiny little holes that you've got to put the safety wire through.

It was fine most of the time but on one particular plane the carburetor was up where you couldn't see it. You had to safety-wire four nuts holding it on in a tiny spot you couldn't see."

The PT-13 Kaydet trainer plane flown at the beginning of the war carried a Lycoming R-680, nine-cylinder, radial engine rated at 220 horsepower to produce a cruising speed of 106 m.p.h.

By the end of the war George experienced stick time with the legendary North American Aviation P-51D Mustang. "I tell you what," he said with a grin, "every time we got new planes in we had to take them out for pre-flights and test flights."

The sleek Mustang airframe was strapped behind a Packard V-1650-7 water-cooled V-12 fitted with a two-stage supercharger. With the throttled pulled to the "war emergency power" setting, it spun up to 1,720 horsepower and a top speed around 440 m.p.h.

For years after the war, retired P-51s flew successfully in air races. About 200 are still registered with the Federal Aviation Administration.

In his seemingly typical sense of understatement, George downplayed the experience of flying one of the hottest piston-engine airplanes ever produced. Altitude, he said, negates much of the sensation of speed.

It is something that "disappoints you about an airplane when you talk about horsepower. If you start out with a (Piper) Cub or something with 80 horsepower, you think by the time you get to 300 horsepower you would be going somewhere, But the gain in horsepower didn't mean too much as forward speed was concerned," he said.

"Where the power comes in is the maneuvers, the loops and rolls and all that. Without power you can't fly straight up. I flew the P-51 only in short spurts. It is hard for me to say what it was like. It was something I liked and loved. Other people would say, 'You're a damned fool.' I liked to know the limits but I always flew under the limits. You don't get to make but one mistake."

George's brother, Maj. John Falker Briggs, flew the P-51 with the 332nd Fighter Group, the "Red Tails" of Tuskegee Airman lore, out of Italy. While escorting bombers on a 1944 raid he shot down a German Messerschmitt 109.

Briggs graduated from Sumner High School and studied engineering at Stowe Teacher's College in St. Louis. He retired from the Air Force in 1963 then became an FAA air carrier inspector. He died in 2007 at the age of 86.

About 39 young St. Louisans were Tuskegee Airmen, said Yolandea Wood, president of the Hugh J. White Chapter of the Tuskegee Airmen Inc. She believes two are still with us.

White also graduated from Sumner and Stowe before heading to Tuskegee for pilot training. He went to Europe with the 332nd Fighter Group and was shot down on his 35th mission. He remained a prisoner until the end of the war.

After returning home, White graduated from law school, practiced criminal law and was twice elected to the Missouri House of Representatives. He died in 1979.

Wood, who spent much of her childhood in St. Louis, graduated from the U.S. Air Force Academy in 1986 and spent much of her military career as a KC-135 navigator. She retired from the 618th Tanker Airlift Control Center at Scott Air Force Base with the rank of major.

After the war

Young George left the Army with the rank of captain and returned to St. Louis to help run the Carper Casket Company. He briefly continued to fly.

"Right across the (Mississippi) river there was an airport called Lakeside. Me and several other guys started going over there. All they had was Cubs. Most of the planes had about 100 horsepower. I said I could take my car and run that fast," he said.

While the operators would rent him airplanes, he did not feel welcome. "I don't know if you have been somewhere where you can feel the atmosphere like you shouldn't be there. I had enough of that. I didn't go back."

But he continued to have a need for speed. His visited the auto races on the dirt track at Walsh Stadium on Oakland Avenue and started drag racing an Oldsmobile 88 in which he had installed a Cadillac engine.

"I did drag racing for about 12 years. The problem was you weren't winning much money. Not all of the races paid. All you got it is, 'He's a good fella' and some trophies. You can't eat trophies. That got expensive even if you did a lot of your own work."

Daughter Carole said she has heard that "Dad developed some of his drag racing skills running moonshine in his Alabama days."

After his drag racing phase, George found another hobby -- boats. "Boats were my love. They say black people don't like water but I loved water," he said.

He started with a 14-foot boat and continued to acquire larger and larger boats. "At one point I had about 12. My wife told me I made a good collector."

Deciding he wanted a boat that was bigger yet, he acquired a steel houseboat that turned out to be heavy and underpowered. "Later I had one made out of aluminum and put two 350-horspower engines in it with Mercruiser out-drives. It would cruise at 40 m.p.h. at 2,200 r.p.m. The engines weren't straining or burning much gas."

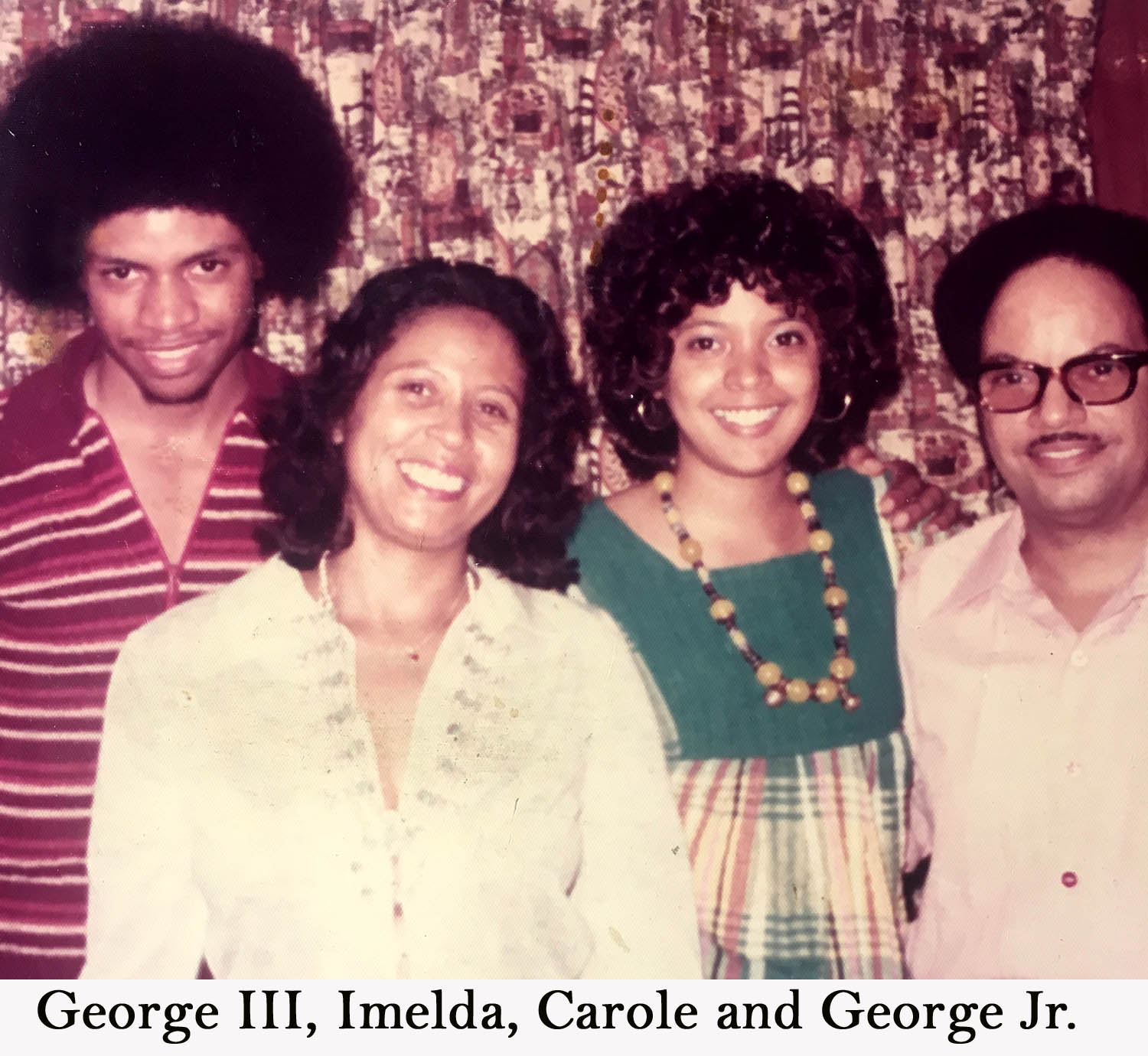

Many Carper family pictures were taken on the houseboats. George and his wife of 64 years, Imelda, raised three children, George III, Jacqueline and Carole. George III passed away in 2009 and Imelda in 2014.

Awareness of the Tuskegee Airmen has been renewed in recent years. In 2007 President George W. Bush awarded Congressional Medals of Honor to Maj. Briggs and Capt. Carper in White House ceremonies that included about 300 of the surviving Airmen. Models of Tuskegee Airman P-51 Mustangs, painted with distinctive red tails and yellow wing stripes, are readily found in hobby shops.

That recognition was rather belated, Carole noted, as most of the Airmen had passed away. "They waited so long -- Uncle Johnny had to have a nurse accompany him in his wheelchair."

George will celebrate his 95th birthday on July 15.

"Dad has always kept himself busy," said daughter Carole. "When he was a kid he had a darkroom in the basement. He had hobbies from photography to mechanics to cars and boats. He also loves jazz. He would never dwell on being a black man in America and thinking, 'I'm catching hell."

She was asked why George seems dismissive of acknowledging his extraordinary contributions to his country. "He loves the attention but he is in a wheelchair now. I don't know if dad looks at himself as a hero. I think he looks at himself as a man who tried to be his best, whatever the circumstances."

"Most of my friends from the service are gone," George said. "I went down there as a little boy of 15 or 16 and most of them were much older."

He danced around a question about any sense of pride he might hold. "I am proud of anything I do, not one particular thing. Some people say the war is over, it doesn't make a difference now. That doesn't bother me."

Moments later he admitted that he had long remembered the men who laughed at the kid who visited Jack Steuby's airport on the Meramec and predicted he was going to fly.

"That made me a better pilot," he said. "You get two feelings when you're flying -- you're proud but you know if you don't do it right you bust your ass."

###