There were momentary flashes of lightning on all sides of the horizon. The milky way appeared like luminous phosphorescent clouds, and Heaven's jeweled tiara of stars glistened below us and above us. Night's queenly brow shimmered with the mellow light of the newborn crescent moon, Starlight and moonlight!

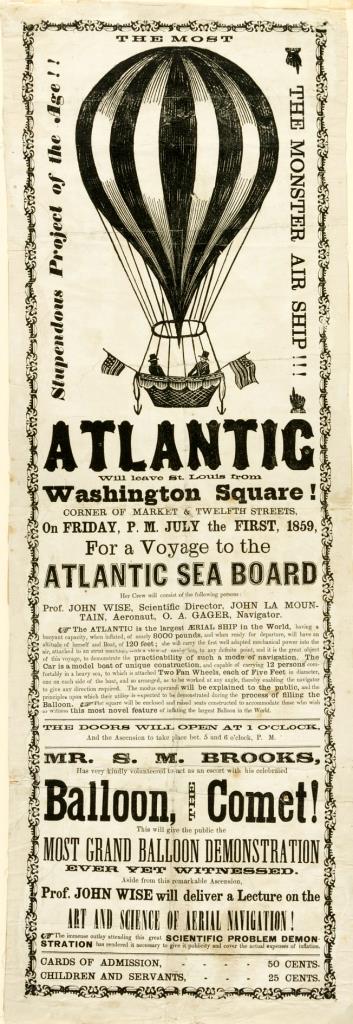

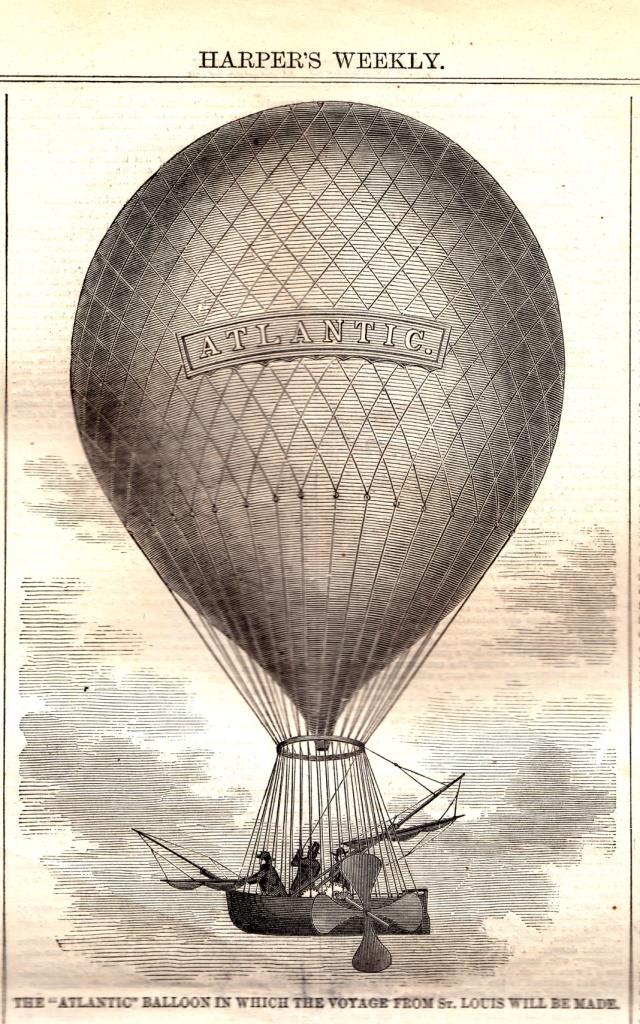

During much of the trip, the voyagers estimated the velocity of their carrying winds at 60 to 90 miles per hour and achieved a maximum altitude of two miles. As changing winds and temperatures caused the balloon to fall and rise, the balloonists released sand ballast or gas to adjust its altitude. At sunrise on the morning following the launch, the balloon passed near Fort Wayne, Indiana. At 5 a.m. the crew spotted Lake Erie. Within three hours the balloon traversed its 250-mile width.

They passed over the Niagara Falls at a height of 10,000 feet. "The falls were quite insignificant, seen from our altitude," Hyde noted.

The storm

As the Atlantic left Niagara Falls behind, ominous clouds appeared in the distance. Hyde recounted his story for a magazine:

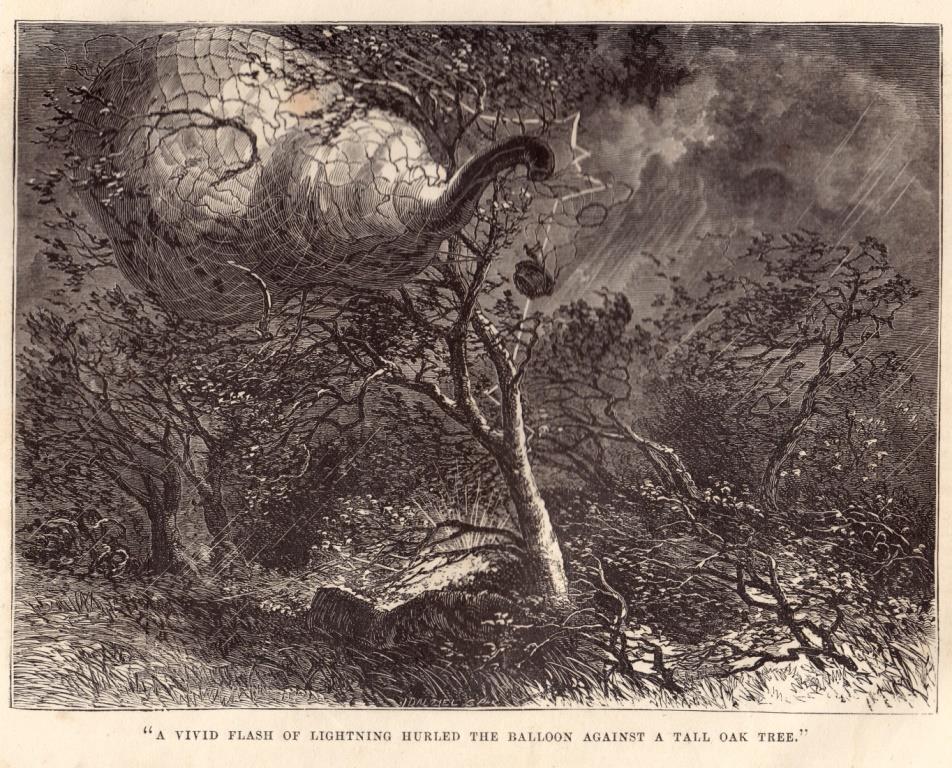

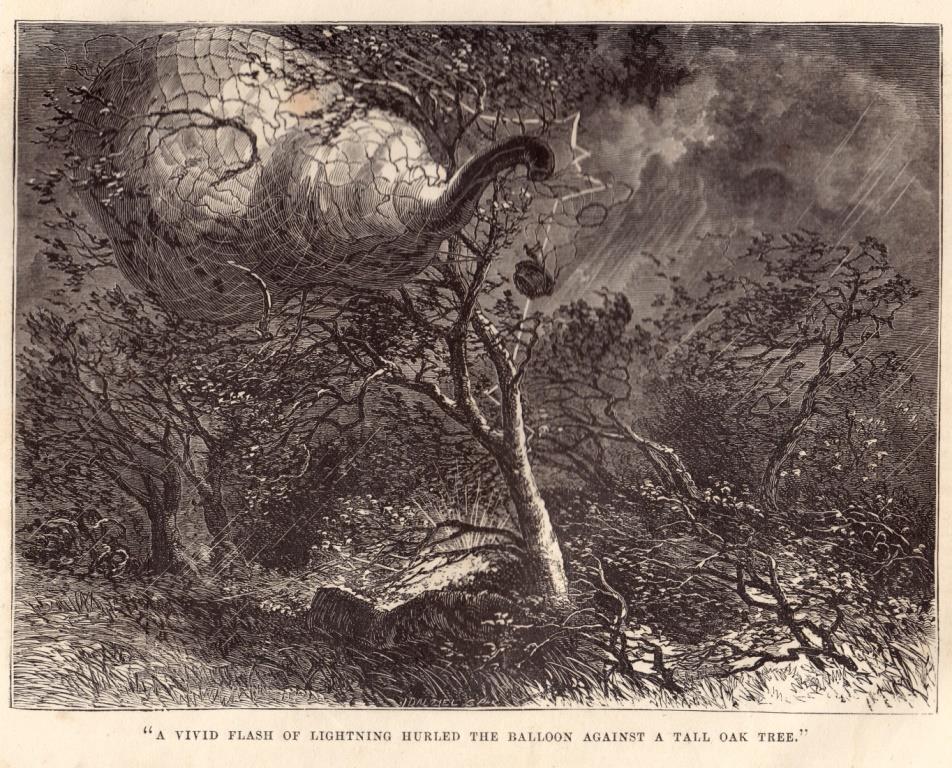

At 10.20 a m. we were skirting along the Canada shore . . . Finding ourselves in the State of New York, but too far north to make the City of New York . . . we descended gradually, but before we got within a thousand feet of the earth we found a most terrific gale sweeping along below. The woods roared like a host of Niagaras, the surface of the earth was rilled with clouds of dust, and I told my friends certain destruction awaited us, if we should touch the earth in that tornado.

The huge ''Atlantic" was making a terrific sweep eastward; already were we near the tops of the trees of tall forest, and I cried out somewhat excitedly, "for God's sake heave overboard anything you can lay your hands on . . . "

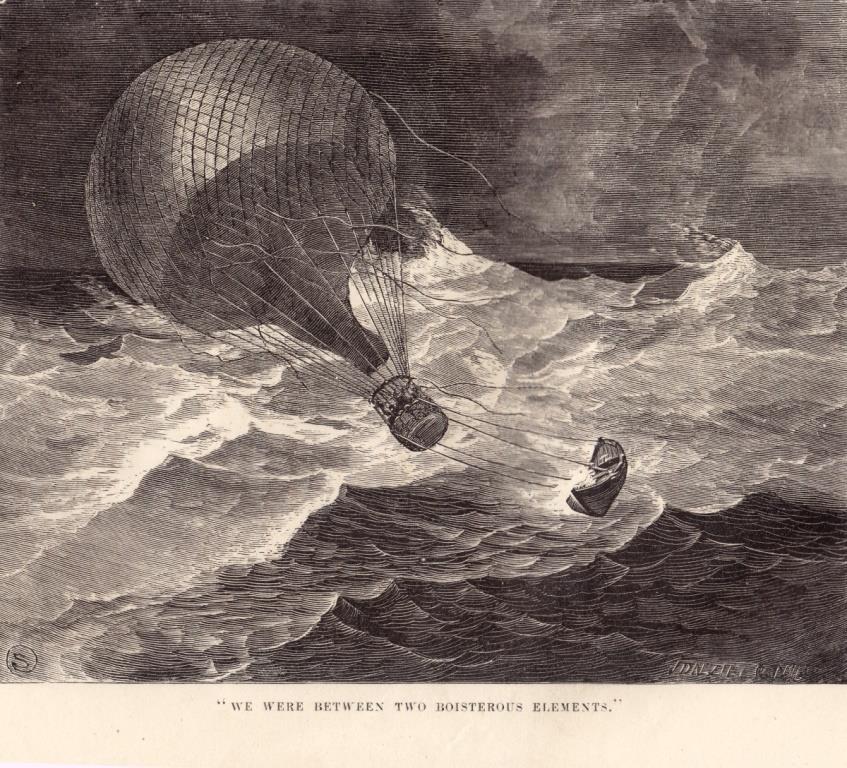

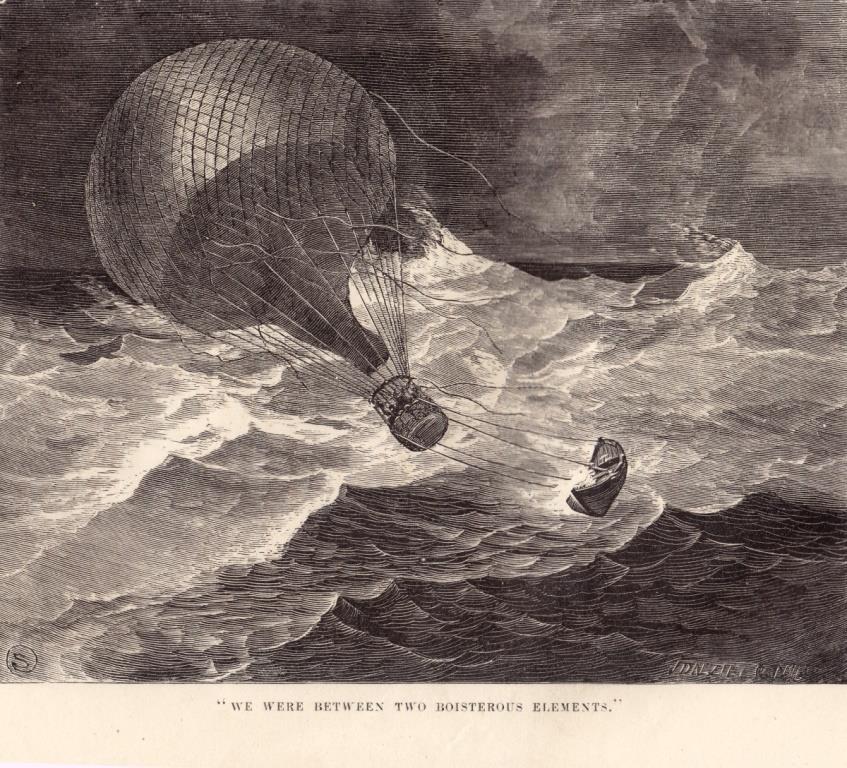

We were fast running on to Lake Ontario, and O! how terrible it was foaming, moaning, and howling . . . I will cut up the boat for ballast, and we can keep above water until we reach the opposite shore," which was near a hundred miles off in the direction we were then going.

Everything now indicated that we should perish in the water or on the land; and our only salvation was to keep afloat until we got out of the gale. We now discerned the shore, some forty miles ahead, peering between a sombre bank of clouds and the water-horizon, but we were sweeping at a fearful rate upon the turbulent water, and, in another moment, crash went the boat upon the water sideways, staving in two of the planks, and giving our whole craft two fearful jerks by two succeeding waves. In another moment we were up a few hundred feet again. . .

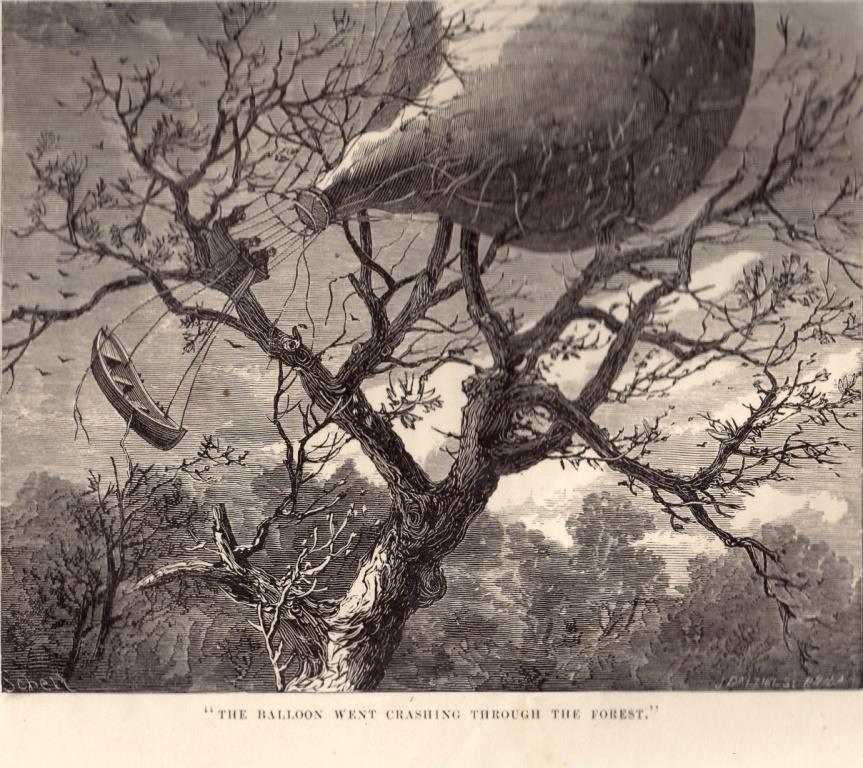

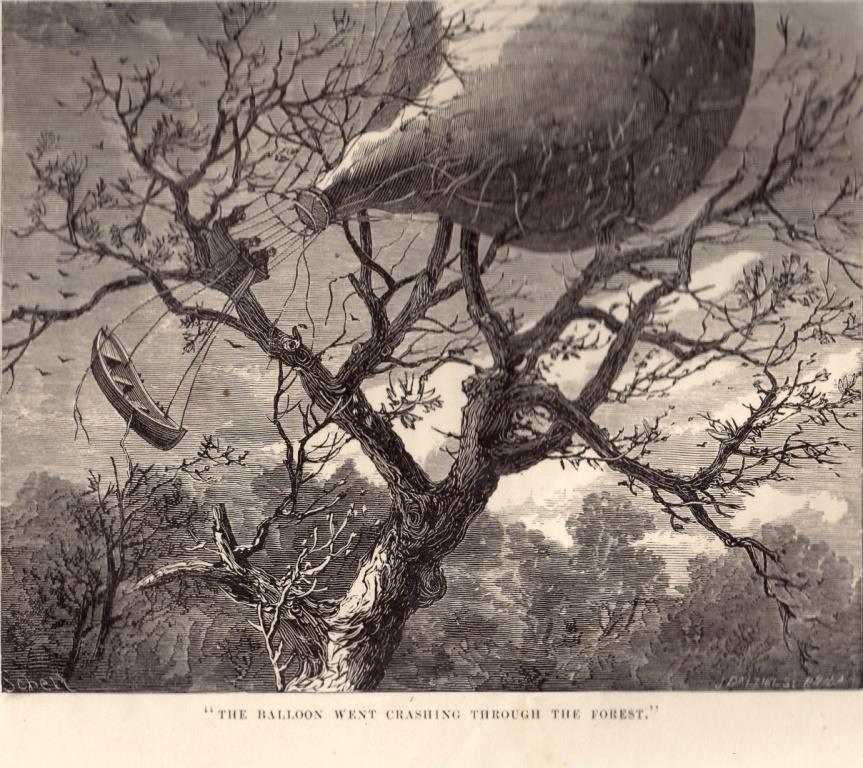

I saw by the swaying to and fro of the lofty trees into which we must inevitably dash, that our worst perils were at hand, but I still had a blind hope that we should be saved . . . We struck within a hundred yards of the water, among some scattered trees . . . hurling through the tree tops at a fearful rate. After dashing along this way for nearly a mile, crashing and breaking down trees, we were dashed most fearfully into the boughs of a tall elm . . .

I saw by the swaying to and fro of the lofty trees into which we must inevitably dash, that our worst perils were at hand, but I still had a blind hope that we should be saved . . . We struck within a hundred yards of the water, among some scattered trees . . . hurling through the tree tops at a fearful rate. After dashing along this way for nearly a mile, crashing and breaking down trees, we were dashed most fearfully into the boughs of a tall elm . . .

It was a fearful plunge, but it left us dangling between heaven and earth, in the most sorrowful plight of machinery that can be imagined. None of us were seriously injured, the many cords the strong hoop made of wood and iron, and the close wicker-work basket saving us from harm, as long as the machinery hung together, and that could not have lasted two minutes longer.

We came to the land, or rather tree, of Mr. T. O. Whitney, Town of Henderson, Jefferson Co., N.Y.

The 1955 American Heritage story offered further details of the landing.

"The four balloonists were safe, their small basket perched precariously in the fork of a giant tree. Below, some half dozen people from the neighborhood who had watched their coming were as much amazed as the aeronauts at this final result of their flight. An elderly lady with spectacles told Wise that she was really surprised and astonished to see so sensible-looking a party as theirs riding in such an outlandish-looking vehicle.

The intrepid quartet now stood up in their basket and gingerly checked their bodies for broken bones.

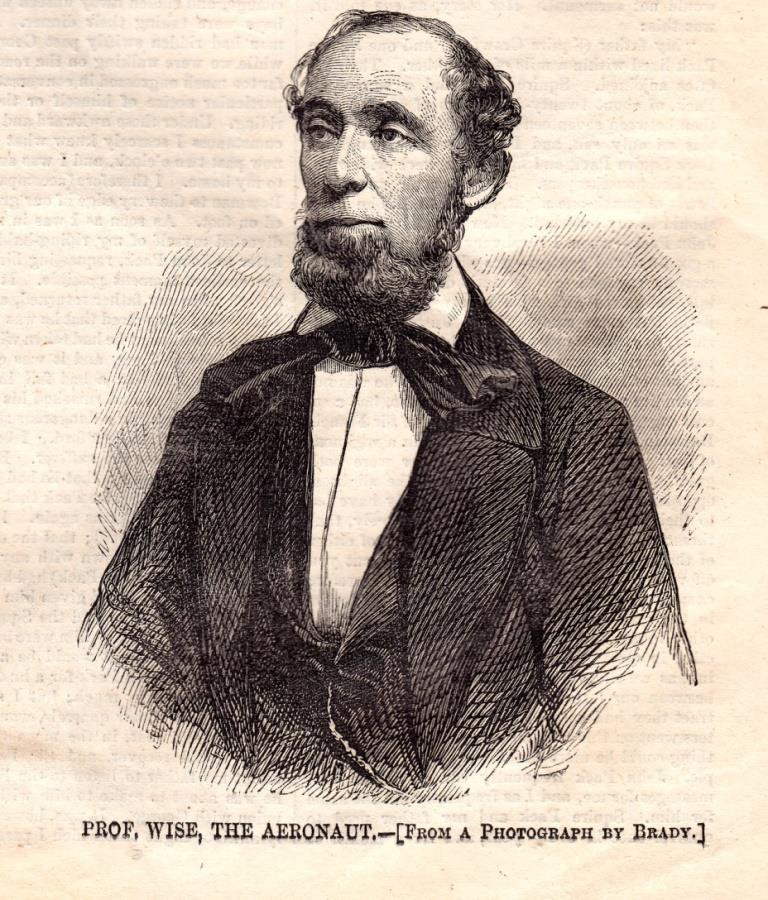

Although this successful voyage of the Atlantic received much favorable publicity, it was many years before John Wise secured financial backing for his trans-ocean flight. At last in 1873 he got it—from a new and somewhat boisterous newspaper, the New York Daily Graphic. Elaborate plans were laid—but the flight was never actually made.

Neither of the other two voyagers, Gager and Hyde, as far as we know, ever set foot in a balloon again.

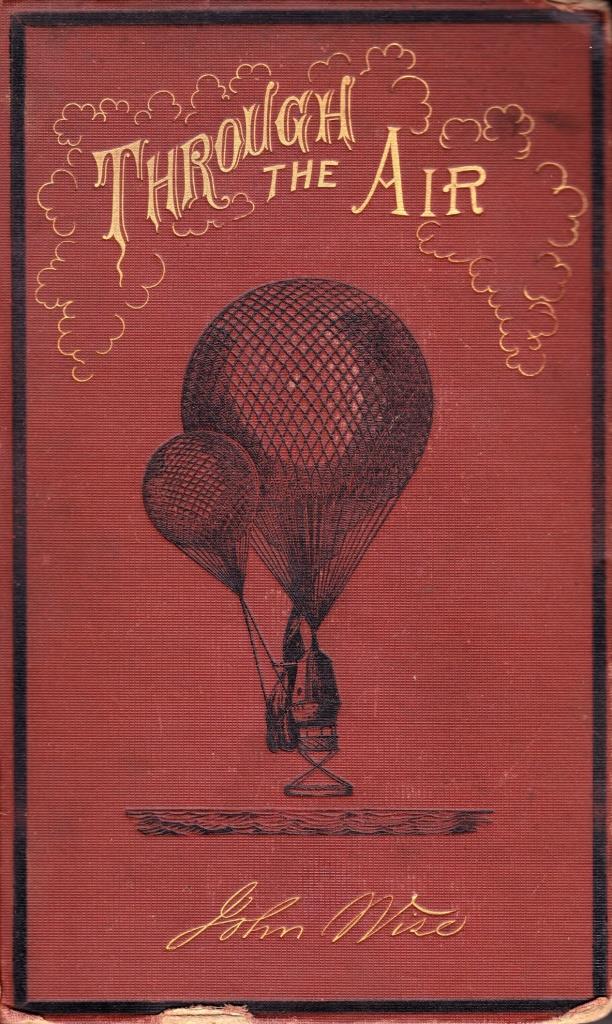

In Wise's book Through the Air, he described the Atlantic's final wrenching moments:

In another moment a limb of the tree, seven or eight inches thick, was torn from its trunk and was swinging in the rigging of the balloon. Another squall, and the air-ship bounded out of the woods and lodged in the side of a high tree, with the limb still hanging to it, and then collapsed. It split open in a number of places, and some of the pieces were carried off high in the air.

Later flights

Wise continued flying until 1879. During a flight when he was 71 years old, his balloon was blown over Lake Michigan and he was never seen again.

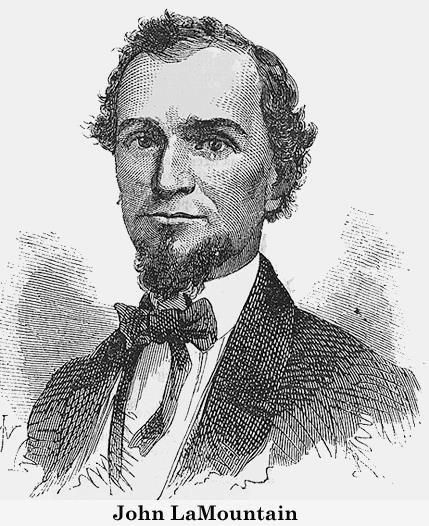

LaMountain bought the remains of the Atlantic after the crash in New York and made repairs. In September 1859 he took another newspaperman, John Haddock of Watertown, N.Y., on a flight across Minnesota and Michigan. Winds unexpectedly carried Atlantic into Canadian wilderness. LaMountain was forced to land and the men spent four days lost in the forest until they were rescued by lumbermen.

Still flying the Atlantic early in the Civil War, LaMountain approached the U.S. Army offering his services for surveillance of enemy movements behind battle lines. He is credited with making the first wartime aerial reconnaissance.

The Atlantic's St. Louis-New York distance record was surpassed in 1900 when Count Henri de La Vaulx of France traveled 1,192 miles in his balloon, Centauri. He departed Vincennes, France, and landed nearly 36 hours later in Korostishev, Russia.

The amazing Mr. Hyde

William Hyde was a respected newspaperman when he volunteered to join the voyage of the Atlantic a few weeks before his 23rd birthday. He was born near Rochester, N.Y. His great-grandfather had served as an officer in the Revolutionary War. His grandfather fought in the War of 1812.

As a young man, Hyde intended to become a teacher and ventured to Lebanon, Ill., to attend McKendree College for two years. He then headed to Transylvania University in Kentucky to study law and became interested in politics. His first published newspaper story, in the Belleville Tribune, concerned U.S. Sen. Stephen Douglas, whose re-election was challenged by Abraham Lincoln and produced the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates.

Hyde served as editor of the Belleville Tribune and then the Sterling (Illinois) Times before he was plucked by the St. Louis Republican to serve as its correspondent in Springfield, Ill., in 1857. After the year's legislative session ended, Hyde was invited to become a reporter in St. Louis. Hyde became assistant editor of the paper in 1860. Upon the death of the paper's editor in 1866, Hyde became editor-in-chief and steered the paper until 1885.

"He managed the paper through the five presidential campaigns that followed, and it may fairly said, so directed its editorial policy and managed its entire course as to largely increase its influence and usefulness," recounted a St. Louis history book.

"In 1885 he made a visit to Europe, taking his family with him, and shortly after his return was appointed by President Cleveland postmaster of St. Louis -- a position whose duties he discharged with the conscientious diligence that marked all of his tasks of trust and responsibility, and in a spirit of fairness and liberality that gained him the respect of his political opponents.

"The fast mail, which has been of so great advantage to St. Louis and the West, is one of the achievements brought about by his personal efforts.

"After the expiration of his term of service he went to St. Joseph and started a daily morning paper called "The Ballot," but the enterprise was not financially successful. He was next called to Salt Lake City to assume the editorship of the Salt Lake "Herald . . . (after) he resigned the editorship of the 'Herald' and returning to St. Louis, accepted a position in the post office under Postmaster Carlisle, continuing literary work at the same time."

In 1897 he was asked to become editor of "The Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis," which remains a valuable reference work for historians.

After his death, a later historical work said of Hyde:

"His friends were accustomed to say that he was absolutely fearless and never blanched before man or condition; and his daring balloon adventure with two companions, on the 1st of July, 1859 -- when he made a voyage from St. Louis to Jefferson County, New York, passing over Lake Erie and Lake Ontario in twenty hours -- was certainly an illustration of this admirable quality.

"Those were intimate with him knew that beneath his strong, robust appearance he was the gentlest of men, and while he was absolutely incorruptible, and savagely intolerant to anyone who approached him with a proposition involving, in the slightest degree, faithlessness to duty or honor, he was patient and considerate to all who fairly claimed his attention, sweet as summer to those he numbered as his friends, and warm-hearted and affectionate to the few who were enshrined in his heart.

"For twenty years he was a leader of the Democracy of the Mississippi Valley, influencing men by both by his forcefulness and tact in personal contact,, and through the press by his masterly editorials. In those days there was hardly an editor in the United States whose utterances commanded to a great extent the attention of the public, and being widely copied, they made him known in journalistic and political circles from one end of the country to the other."

Hyde died on October 30, 1898, at the age of 62. He still held the record for man's longest flight.

HOME