Click to print

JEFFERSON CITY --

After two decades of kicking rattling cans of change along roads sprouting potholes, might anti-tax Missouri be prepared to raise its motor fuel taxes to start catching up on delinquent transportation needs?

A new study on the state's unaddressed road and bridge issues has prompted introduction of 10 bills and resolutions in the current session of the Missouri General Assembly.

Missouri excels in prime location and transportation resources stated the bipartisan 21st Century Missouri Transportation System Task Force, which held meetings across the state last year and issued a 67-page report on Jan. 1.

But, the report continued, Missouri also trails most states in funding for roads and bridges -- ranking nearly last, actually. The result is an estimated annual shortfall of $825 million in spending for repairs and new construction.

The tax force called upon legislators to place a fuel tax increase on the ballot, as required by the state Constitution, and to consider other means of raising future funding. They issued this summary to the state's tax-phobic leaders:

Although Missouri has the seventh-largest state highway system in America, with the sixth-highest number of bridges, the state funds its transportation system at only 47th in the nation in revenue per mile. Consequently, our aging transportation-infrastructure system is deteriorating, the safety of highway travelers is put at risk, and declining transportation reliability is threatening economic growth, despite the best efforts of the Missouri Department of Transportation.

This funding deficiency did not arise overnight, but over a period of years, as past political leaders have failed to recognize or act upon the need to address transportation-infrastructure investment. Many people who testified at the Task Force’s hearings used the idiom of “kicking the can down the road” to describe the state’s approach to addressing (or not addressing) transportation funding in recent years.

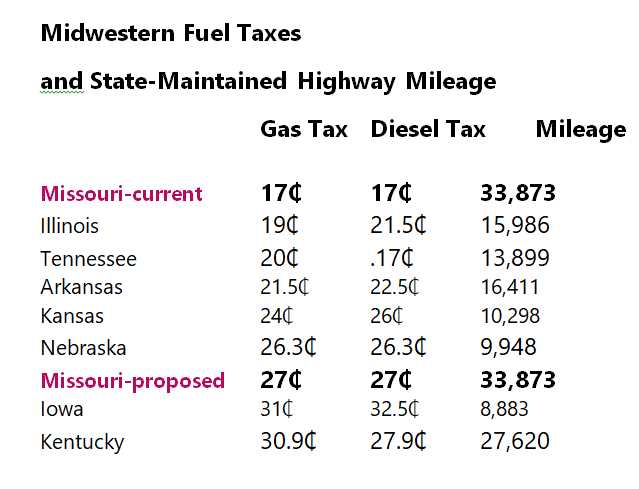

The 23-member task force was chaired by Rep. Kevin Corlew, R-Kansas City. The vice-chairman, Sen. David Schatz, R-Sullivan, has introduced Senate Bill 734 in the current session of the General Assembly. The bill would add 10 cents per gallon to Missouri's 17-cent fuel tax, which was last changed in 1996.

Other bills would raise the tax gasoline from in amounts ranging from 2 cents to 17 cents per gallon.

One bill, curiously, would raise the fuel tax in 3-cent increments if the increases were offset by cuts in state income taxes, which come from and go into entirely different funding pools -- like paying more for home electricity only if it can be deducted from the natural gas bills.

The time may have come for an increased tax even in Missouri, which currently has the fourth-lowest fuel tax in the country. Inflation has reduced its purchasing power to the 1996 equivalent of 8 cents, the Task Force reported.

An increase has been endorsed by Missouri AAA as well as some of the lobbying organizations that often dictate outcomes of such matters, including the trucking industry and Missouri Farm Bureau.

"AAA has long recognized that the Missouri Department of Transportation needed additional funding to maintain and improve the state's roads," said Mike Right, vice president of public affairs for AAA Missouri. "What should also be obvious is that with population growth and development outside the urban cores, roadway needs continue."

Some proposals would increase the tax on diesel fuel by 12 cents while the gasoline tax goes up 10 cents because it is said the heavy trucks put more wear and tear on roads and bridges. The trucking industry holds that trucks already pay more fuel taxes per mile because they use at least three times as many gallons of fuel per mile than automobiles.

The federal government is not expected to assist in addressing road and bridge deficiencies nationally.

While President Trump has proposed a ten-year plan to spend $1.5 trillion on infrastructure, he proposes that the federal government contribute just $20 billion annually (or $200 billion over ten years).

The task force notes that 27 states have increased fuel taxes since 2013.

Miles and Miles

"Missouri has a large highway system that includes 33,884 miles of roadway (America’s seventh-largest state highway system); and 10,394 bridges (the sixth-most nationally). The highway system is aging. The oldest stretches of the Interstate highway system in the state, for example, were built in the 1950s with a 20-year life expectancy. Moreover, a large portion of state-maintained bridges have surpassed their 50-year design lives," according to the task force.

Missouri ranks 47th out of 50 states in terms of transportation revenues per centerline mile of state-maintained highway. (Bordering states have two to five times as much revenue per centerline mile.) And Missouri does not have the benefit of user-based toll revenues (or federal toll credits) collected in states such as Kansas, Oklahoma, Kentucky, Illinois, Indiana and Ohio.

The fuel tax is the largest source of funding for roads and is said to cost the average resident $30 monthly. The 10-cent increase would restore the tax's equivalent buying power to what it was in 1996.

The Task Force wrote that the shortfall in infrastructure investment costs the state through increased traffic congestion, wasted fuel, increased crash risks and vehicle damage and tire wear resulting from rough roads.

"Roads and bridges aren’t being improved sufficiently; The transportation system isn’t as safe as it could be; Economic growth is being stifled; Travelers too often are delayed because of traffic congestion; Interstate highways need to be reconstructed but instead are merely maintained; Multimodal transportation options are neither enhanced nor increased."

The proposed tax increase would create about $430 million in new revenue, which would be split among the state, county and local highway departments.

"The proposed increase would still keep Missouri competitive with surrounding states and nationally," t

he Task Force reported.

City and county roads would receive a portion of the increased tax revenue.

The Missouri Constitution allocates 70 percent of the revenues to the state, 15 percent to cities, and 15 percent to counties. Thus, the state road fund would receive approximately $2.6 billion, while cities and counties would each receive approximately $557 million.

The Task Force identified the fuel increase as the first step in longer-term planning for future transportation funding needs.

Missouri Transportation Resources

Because of existing strengths, Missouri is poised (with strategic policymaking and proper investment) to have a world-class transportation and to be a leader in travel, logistics, and freight distribution. Missouri has a large system of road, highways, and bridges, including major interstate highway corridors that provide easy access for freight transportation.

In addition to the immediate fuel tax increase, the Task Force recommends that the General Assembly consider additional options in the future, including:

* Increased registration fees for electric vehicles and excise fees or taxes on electric charging stations and systems;

* Increases to user fees for driver’s licenses and vehicle registrations;

* Indexing motor fuel taxes and licensing and registration fees to inflation;

* Basing vehicle-registration fees on fuel efficiency (MPG) instead of horsepower;

* Dedicating a portion of Internet sales-tax revenue to transportation purposes;

* Consider tolling for construction of major bridges;

* Consider mileage-based road-user charges; and

* Enable local construction excise taxes.

Missouri's highway ledger holds 5,517 miles of interstates and "major routes," of which about 90 percent are rated in "good" condition. Interstate 70, however, "needs to be reconstructed with added capacity to handle mounting levels of traffic, especially long-haul trucks. The project, though, has been and continues to be unaffordable. The state’s other six interstates will also be facing improvement/preservation needs in the coming years."

Missouri has 17,450 miles of "minor" routes with 80 percent rated "good."

The state's scenic, rolling terrain requires a lot of bridges that create potentially expensive maintenance burdens. The task forces states:

"Missouri has 10,403 bridges of varying sizes, including 207 major bridges that are longer than 1,000 feet (about the length of three football fields). Currently, 883 bridges are in poor condition. MoDOT inspects these bridges on a regular basis to ensure they’re safe for travelers. If a bridge is unsafe, it is closed until repairs can be made. Missouri also has 1,253 weight-restricted bridges, with 466 of them also in poor condition."

Missouri roads and highways carry 74 billion miles of vehicle travel and $371 billion worth of freight annually, the report adds. "The nation’s second- and third-largest railroad hub centers are at either side of the state, in Kansas City and St. Louis, respectively. And Missouri has more than 1,000 miles of inland waterways with the Mississippi and Missouri rivers combined, and 14 public port authorities facilitate commerce on these rivers."

There is also recognition that the federal government is looking to states to self-fund more of their transportation needs as the federal Highway Trust Fund deficit grows.

The federal gasoline tax (18.3 cents per gallon on gasoline and 24.3 cents per gallon on diesel), which is the primary source of federal transportation dollars, has not been adjusted since 1993. Under the current political environment it is not going to be adjusted.

The task report lists the 2016 budget allocations for Missouri transportation funds: $1.4 billion (58 percent) to construct, operate and maintain the system; $408 million (17 percent) to cities and counties; $280 million (11 percent) for debt service; $230 million (9 percent) to the State Highway Patrol to administer and enforce state motor vehicle laws and traffic regulations; and $20 million to the Missouri Department of Revenue to collect and administer the revenue.

About four percent of revenues—derived from general appropriations and not the State

Road Fund—support "multimodal" transportation such as rail, transit, waterways and ports.

There is widely-held consensus that more transportation funding is needed in Missouri, the report states. "Increasing the motor fuels tax was mentioned the most during testimony as the preferred form of funding increase. Several reasons were cited, including:

The motor fuel tax is user-based; Consumers recognize its significant nexus to travel on the highway system; The tax is paid by Missouri citizens and out-of-state motorists as they travel through Missouri; Missouri already has a constitutional lockbox on a motor fuel tax, such that the generated revenue can be used only for the highway system;

"There is an efficient means of collecting the revenue already in place; Missouri’s current motor fuels tax burden is low (46th in the nation); The average Missouri driver would only pay an additional $5 per month if the motor fuels tax was increased; and, Even with this modest increase, Missouri would remain competitive with its neighboring states.

"The Task Force further recommends that the General Assembly consider adjusting or indexing the flat gasoline and diesel excise tax to account for future inflation and fuel-efficiency improvements in the light vehicle fleet . . . 20 states now index their state motor fuel tax to keep up with growing costs and inflation.

"The Task Force recognizes that, under the state’s Hancock Amendment, it will be necessary to put a proposed increase of 10 cents per gallon on gas and 12 cents per gallon on diesel to a vote of the people."

###

R Stoff

HOME

Subscrbe to Our Newsletter

Pediatric traffic deaths decrease sharply as use of child safety seats and seat belts increases, according to two recent studies that examined child safety restraint use.

While outcomes varied dramatically by state along with estimated use of safety equipment, state laws regarding child seat and safety belt use had no quantifiable effect on usage or fatality statistics. Statistics for Missouri and Illinois closely tracked the national data.

One study found that 20 percent of children younger than 15 involved in fatal accidents were not properly restrained. Reducing that rate to 10 percent could avoid about 232 pediatric deaths annually, the study concluded.

Researchers used federal statistics to measure outcomes for children who were passengers in vehicles involved in accidents that caused at least one fatality. The pediatric motor vehicle mortality rate ranged from 0.25 per 100,000 children in the population in Massachusetts to 3.23 in Mississippi. The national rate was 0.94.

The project, published recently in the Journal of Pediatrics, was conducted by researchers at the Center for Surgery and Public Health at Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

From 2010 through 2014 there were 2,885 fatalities among 18,116 children who were passengers in vehicles involved in fatal crashes

"On average across all states, 20 percent of children involved in a fatal crash were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained at the time of the crash, 13 percent were inappropriately seated in the front seat and nearly 9 percent of drivers carrying a child passenger were under the influence of alcohol," wrote lead author Lindsey L. Wolf, M.D., M.P.H., of Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

"Crashes were most likely to occur on state highways (35 percent) and on roads classified as rural by the Federal Highway Authority (62 percent)," the paper continued."There was substantial state-level variation of the key predictors . . . The percentage of children who were unrestrained or inappropriately restrained varied from 2 percent in New Hampshire to 38 percent in Mississippi."

Protective effects were found for children riding out crashes in vans -- the percentages of fatalities by vehicle type were vans, 14 percent; pickup trucks, 17 percent; sport utility vehicles, 24 percent; and cars, 42 percent.

Speed

Children were less likely to die in crashes occurring on highways with speed limits of 65 to 80 miles per hour. About 24 percent of pediatric fatalities occurred on higher-speed interstates while 52 percent took place on highways posted at 45 to 60 m.p.h.

"After adjusting for the other factors . . . the independent effect of speed limit became protective," the paper said. "This may reflect unmeasured characteristics of roads with high speed limits, such as better maintenance, fewer curves, wider lanes and shoulders and more expeditious access by emergency medical vehicles."

State child restraint laws vary in strictness, the ages of infants and children who are covered, the size of fines and the method of enforcement -- some states allow child restraint citations to be written as a primary offense while others permit only "secondary enforcement" if the driver is being ticketed for another offense.

"Seat belt and car seat laws did not have significant associations with the outcomes," the Brigham-Texas paper explained. "This finding suggests that there may be a gap between legislation and enforcement of these regulations."

However, the study stated, "State policy characteristics are an important mechanism to decrease pediatric deaths from motor vehicle crashes. Further, full implementation of policies is necessary to ensure child safety--uneven implementation and enforcement may contribute to the state-level variation we observed."

The existence of state laws allowing red light cameras at intersections was associated with lower rates of pediatric crash fatalities, but the authors were stumped for an explanation. They noted that evidence on the effectiveness of red light cameras in general is questionable.

"Prior evaluations of red light cameras have mixed results . . . there has been methodological critique of the published studies. To date there are no randomized, controlled trials published on red light cameras," the authors wrote.

Their best guess for a link? "Having legislation in place regarding red light cameras may be a proxy for a state's overall interest in prioritizing legislation and enforcement of traffic safety measures."

Missouri and Illinois

Over the 2010-2014 period covered by this research, 473 children were involved in a fatal crash in Illinois and 75 died. In Missouri 17 of the 539 children involved in such crashes died.

In Illinois, 22 percent of children involved in fatal accidents were unrestrained as were 20 percent of Missouri children. Both states experience the risks of rural roads -- 45 percent of fatal pediatric accidents in Illinois and 62 percent in Missouri occurred in rural areas. As for interstates with 65- to 80-m.p.h. speed limits, only 11 percent of fatal accidents in Illinois and 19 percent in Missouri were recorded on the higher-speed pavement.

The study compared state outcomes by AAMR, or "age-adjusted, mean motor-vehicle-crash-related pediatric mortality per 100,000 children." In Illinois the rate was 0.60 per 100,000; in Missouri it was 1.50.

The states with the highest mortality rates were Mississippi, 3.23; Alabama, 2.71; Montana, 2.23; West Virginia, 2.16; and Oklahoma, 2.02. The lowest rates resulted in Massachusetts, 0.25; New York, 0.29; New Jersey, 0.32; Rhode Island, 0.33; and Washington, 0.33.

Regionally, the rates were 0.89 for the Midwestern states; 0.39 in the Northeast; 1.34 in the South; and 0.76 in the West.

Regionally, the rates were 0.89 for the Midwestern states; 0.39 in the Northeast; 1.34 in the South; and 0.76 in the West.

Another View

"We cannot say with high statistical certainty whether the probability of dying in a fatal accident has decreased due to the (child safety) laws," stated a paper published this year in the Journal of Policy Analysis and Management.

The report, "U.S. Child Safety Seat Laws: Are They Effective, and Who Complies," was produced by Lauren E. Jones of the Ohio State University Department of Human Sciences and Nicolas R. Ziebarth of the Cornell University Department of Policy Analysis and Management.

"Our most conservative estimates suggest that the laws increase child safety seat use by about 50 percent . . . . our estimates suggest that at least 2.7 million (U.S.) children under the age of eight ride in safety seats each year as a result of more stringent laws," this report stated. "We also find suggestive evidence that the increasingly strict legislation reduced the risk of dying in a fatal crash, although our coefficient estimates are generally small in magnitude and imprecisely estimated."

Much of the increased use of child seats may come from parents who previously were buckling children into seat belts. "Our findings primarily show a substitution effect . . . rather than a substantial decrease in the share of unrestrained children. This finding also may be an explanation for why we do not find a large, statistically significant impact of the laws on the likelihood that children die in fatal accidents."

This paper concluded that data cannot demonstrate that safety seat laws save more than 39 children's lives annually. The authors also suggest that higher fines are not a meaningful deterrent. "Other regulatory tools, such as information campaigns, may be effective in producing the intended behavioral changes among parents."

Regional laws

Neither Missouri nor Illinois laws limit child restraint citations to secondary enforcement. According to the Brigham and Texas research paper, state fines for an initial violation of child safety laws range nationally from $10 to $500.

Missouri Child Restraint Law

(from Missouri Department of Transportation)

Children less than 4 years old or less than 40 pounds must be in an appropriate child safety seat.

Children ages 4 through 7 who weigh at least 40 pounds must be in an appropriate child safety seat or booster seat unless they are 80 pounds or 4'9" tall.

Children 8 and over or weighing at least 80 pounds or at least 4’9” tall are required to be secured by a safety belt or buckled into an appropriate booster seat.

The fine for violating this law is $50 plus court costs

Illinois Child Restrain Law

(from Illinois State Police)

In Illinois, the law states that each driver and passenger of a motor vehicle must wear a properly adjusted and fastened seat safety belt.

Provides that whenever a person is transporting a child under age 8, the person is responsible for properly securing the child in an appropriate child restraint system, which includes a booster seat.

Every person, when transporting a child 8 years of age or older, but under age 16, is responsible for properly securing that child in a seat belt. If the vehicle used to transport children under eight years of age is equipped with lap belts only in the back seat and the child weighs more than 40 pounds, the child may be transported in the back seat wearing a lap belt only. If a combination lap and shoulder belt is available, the child must be secured in a booster seat.

Violators of the Child Passenger Protection Act are subject to a $75 fine for the first offense and are eligible for court supervision if they provide the court with documented proof from a child safety seat technician of a properly installed child restraint system and completion of an instructional course on the installation of that restraint system. A subsequent violation is a petty offense with a $200 fine and not eligible for court supervision.

###

R Stoff

HOME

Subscrbe to Our Newsletter

Subscribe to our Newsletter by clicking here.

Updated June 27, 2018

Email: info@motorcomag.com

Advertise with us

Home | Motoring | Touring | Railroad News | Motorsports | Marine News | Aviation | Traffic Law | Contact Us | About Us